Patients have long said that diets can relieve symptoms of diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Many ALS patients take supplements in varying amounts and types. These claims have long been derided by scientists, yet scientists are now starting to change their minds.

The authors of a new scientific article therefore investigated whether a high fiber diet influences microglial function in mouse models of Parkinson's disease that overexpress α-synuclein. These mice are called ASO (α-synuclein overexpressing) mice.

Parkinson's disease is a disease characterized by α-synuclein pathology and/or dopamine deficiency resulting from degeneration of the substantia nigra (a region of the midbrain).

Although Parkinson's disease is primarily classified as a brain disorder, 70-80% of patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms, primarily constipation, but also abdominal pain and increased intestinal permeability which usually manifest in prodromal stages (Forsyth et al. 2011; Yang et al 2019).

Braak postulated nearly 20 years ago that α-synuclein aggregation can begin in the gastrointestinal tract or olfactory bulb, and eventually reach the brainstem, substantia nigra, and neocortex via the vagus nerve ( Braak et al. 2003).

A growing body of evidence supports the potential for gut-to-brain spread of α-synuclein pathology in rodents (S. Kim et al. 2019; B. Liu et al. 2017; Svensson et al. 2015).

The vagus nerve, a long winding nerve, is a major two-way information signaling pathway between the gut and the brain. Vagotomy is the surgical section of the pneumogastric nerve, or vagus nerve, at the level of the abdomen. Vagotomy has been used for decades and most patients who have had such surgery and are still alive are now elderly. A Swedish registry study investigated the risk of Parkinson's disease in patients who underwent vagotomy and hypothesized that truncal vagotomy is associated with a protective effect.

The scientists found that the risk of Parkinson's disease was indeed reduced in patients who underwent a complete truncal vagotomy, whereas there was no risk reduction in those who underwent a selective vagotomy. The risk of Parkinson's disease is also reduced after truncal vagotomy compared to the general population. These epidemiological findings are important and support the hypothesis that Parkinson's disease begins in the gut and not initially in the brain. This provides further evidence for the involvement of the vagus nerve in disease development.

Many important chemical compounds (nowadays we say "molecular" to make it sound important) are produced in the intestine and end up in the brain via the bloodstream. Many of them are made or have their production regulated by gut microbes.

These include short chain fatty acids tryptophan, leptin and ghrelin. Short chain fatty acids include butyrate, propionate and acetate. Butyrate is a known inhibitor of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and in doing so acts as an epigenetic regulator. Cytokines, key immune-regulating molecules produced in the gut, can travel through the bloodstream and influence brain function, particularly in regions of the brain where the blood-brain barrier is deficient.

Among other effects, microbial food metabolites can modulate the activation of microglia, these nerve cells which are essential for the survival of neurons are implicated in Parkinson's disease. Microglia respond to signals from inside the brain, but also receive information from the periphery, including the gut microbiome (Abdel88 Haq et al. 2019). Microglia from germ-free adult mice show an immature gene expression profile and do not respond adequately to immunostimulants (Erny et al. 2015; Thion et al. 2018). However, if these germ-free mice are fed a mixture of short-chain fatty acids, microglial maturation is restored (Erny et al. 2015).

The gut microbiota is a virtual organ that produces a myriad of molecules needed by the brain and other organs. Humans and microbes are in a symbiotic relationship, humans feed the microbes, and microbes in turn provide essential molecules.

The phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes represent approximately 80% of total human gut microbiota. The genera of the Firmicutes phylum include Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Clostridium, Enterococcus, and Ruminicoccus. The phylum Bacteroidetes mainly includes the genera Bacteroides and Prevotella.

The phylum Actinobacterium is dominated by the genus Bifidobacterium. Bifidobacteria and lactobacilli are generally considered beneficial bacteria and are frequently sold as probiotic supplements. Strains of the genus Clostridium or lipopolysaccharide taxa such as Enterobacteriaceae have been associated with disease states in many neurodegenerative diseases including ALS (Charcot's disease).

Similarly but somewhat controversially, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which explores the relationship between the two dominant phyla, has been associated with various neurodegenerative pathologies.

So, the intestinal microbiome is altered in Parkinson's disease. It is found in mice models of Parkinson's disease (the mice have been genetically engineered to carry a disease resembling that of Parkinson's) that the fecal levels of short-chain fatty acids are different in mice with Parkinson's disease and mice. healthy. It is the intestinal bacteria that transform dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids by fermentation.

The authors designed personalized high-fiber diets, each containing 20% of a prebiotic blend of two or three dietary fibers designed to support the growth of 5 distinct gut bacterial taxa and stimulate the production of short-chain fatty acids based on of faecal fermentation in vitro.

The scientists then observed broad changes at the microbial phylum and genus level after administration of a prebiotic diet, displaying an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes in mice fed a prebiotic diet, resulting in a lower Firmicutes ratio. /Bacteroidetes (F/B) that has been associated with general features of metabolic health.

Interestingly, Bacteroidetes have been shown to be reduced in Parkinson's patients compared to age-matched controls, suggesting that the prebiotic may counteract this effect (Unger et al. 2016). Additionally, they observed a decrease in proteobacteria, a phylum often increased in dysbiosis and inflammation and elevated in fecal samples from patients with Parkinson's disease (Keshavarzian et al. 2015; Shin, Whon, and Bae 2015).

A fiber-rich prebiotic diet attenuates motor deficits and reduces α-synuclein aggregation in the substantia nigra of mice.

Meanwhile, the gut microbiome of ASO mice adopts a health-correlated profile upon prebiotic treatment, which also reduces microglial activation.

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of microglia from the substantia nigra and striatum reveals increased pro-inflammatory signaling and reduced homeostatic responses in ASO mice compared to their wild-type counterparts on a standard diet.

Prebiotic feeding reverses pathogenic microglial states in ASO mice and promotes expansion of microglia's disease-associated protective macrophage (DAM) subsets.

Microglia are dependent on colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling for development, maintenance and proliferation (Elmore et al. 2014).

To test the opposite effect: If depletion of microglia eliminated the beneficial effects of prebiotics, the authors added PLX5622 to the diet of mice aged 5 to 22 weeks and quantified the number of IBA1+ microglia in various brain regions. PLX5622 is a brain-penetrating CSF1R inhibitor that can deplete microglia with no observed effects on behavior or cognition (Elmore et al. 2014).

Depletion of microglia using a CSF1R inhibitor effectively eliminated the beneficial effects of prebiotics and restored motor deficits in ASO mice despite a prebiotic diet.

These studies reveal a novel microglia-dependent interaction between diet and motor Parkinson's disease in mice, findings that may have implications for neuroinflammation and Parkinson's disease.

Prebiotics present a potentially promising therapeutic approach, as diet contributes significantly to the composition of the microbiome and epidemiological evidence has linked high fiber diets to reduced risk of developing Parkinson's disease (Boulos et al 2019).

While increased vegetable intake and adherence to a Mediterranean diet are associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease, people consuming a low-fiber, highly processed Western diet have an increased risk of being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. (Alcalay et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2007; Molsberry et al. 2020).

Several ongoing clinical trials are exploring the beneficial effects of probiotics and prebiotics on Parkinson's disease outcomes. Acting on the diet or the microbiome can help relieve the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Scientists in a new publication, aimed to determine whether the risk of Parkinson disease increases as diabetes progresses among patients with type 2 Diabetes mellitus.

Scientists in a new publication, aimed to determine whether the risk of Parkinson disease increases as diabetes progresses among patients with type 2 Diabetes mellitus.

The imaging analyzes that this study will produce, will make it possible to define a subgroup of patients with Parkinson's disease who will have benefited from the treatment and will help to define rules about when using this therapy in order to avoid unnecessary interventions.

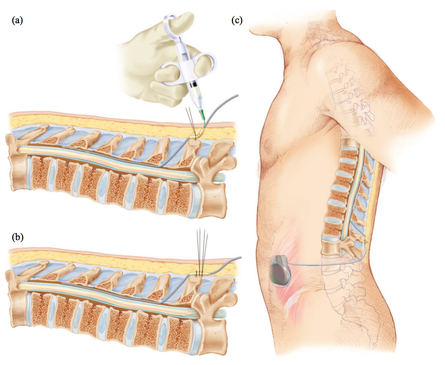

The imaging analyzes that this study will produce, will make it possible to define a subgroup of patients with Parkinson's disease who will have benefited from the treatment and will help to define rules about when using this therapy in order to avoid unnecessary interventions. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical procedure involving the placement of a medical device called a neurostimulator, which sends electrical impulses, via implanted electrodes, to specific targets in the brain (the cerebral nucleus) for treatment movement disorders, including Parkinson's disease. illness, essential tremor, dystonia, and other conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and epilepsy. Its underlying principles and mechanisms are not fully understood.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical procedure involving the placement of a medical device called a neurostimulator, which sends electrical impulses, via implanted electrodes, to specific targets in the brain (the cerebral nucleus) for treatment movement disorders, including Parkinson's disease. illness, essential tremor, dystonia, and other conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and epilepsy. Its underlying principles and mechanisms are not fully understood.