Something is wrong with clinical trials for ALS. It seems difficult, if not impossible, to do worse than current experts in the field. The situation is similar for other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

Over 700 clinical trials, nearly 500 of which are interventional studies [15], have been conducted over the past 15 years on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In the case of Alzheimer's, there have been over 1900 interventional clinical trials and over 2000 of them for Parkinson's disease.

The cumulative cost of these unsuccessful attempts is colossal.

While the average success rate for a phase III clinical trial is over 40%, it is close to zero for neurodegenerative diseases.

In fact, there have been more than 80 negative phase III clinical trials in the case of ALS [14].

The public might expect it to be truly unlikely that experts would fail 500 times in a row, or fail 82 times in Phase III, without any success, when the success rate of phase III clinical trials is close to 50%.

Is it an exaggeration to say that this huge number of failures means that not only do we have no idea of the cause and mechanism of this disease, but that experts in charge have no clues about this type of disease?

One of the first paradigms was that since ALS is caused by the death of upper motor neurons (it's the medical definition of ALS), drugs and treatments for stroke should be effective. It shows the thinking of a doctor, not a biologist.

It has been the main paradigm for decades. There is indeed good reason to think that ALS is similar to an extremely slow stroke. In particular, it mainly occurs in the elderly and the symptoms start locally, for example in the muscle of the hand called the thenar. The symptoms then reach increasingly larger areas of the anatomy as the disease develops.

One of the two drugs approved for ALS, Edaravone, is an intravenous drug used to aid healing after stroke.

In line with this paradigm that says ALS is a kind of stroke, oxidative stress has long been suspected to be a major factor in the spread of the disease. This is why Rilutek has been approved for ALS.

Then, over the last century, there has been the extraordinary expansion of molecular biology. Biologists then, considerably surpassed physicians in numbers and publications. Biologists became the de-facto experts in ALS.

The promise of molecular biology is indeed revolutionary, and that is to find a simple solution to any non-contagious disease.

It is also a promise of considerable simplicity in tooling, which seems to come out of a kitchen rather than from a sophisticated laboratory. In particular, it becomes possible for biologist students to publish on these subjects a few years earlier than if they were studying medicine.

Molecular biology involves a complete paradigm shift in the way we think about ALS disease.

The brains, the nerves and the muscles are forgotten. The cells, whose internal mechanisms are however still largely unknown at the end of the XX century, are rejected as irrelevant in a process of thought which is centered on the translation of the genome in proteins.

The blindness towards medicine, is however difficult to understand for neurodegenerative diseases, because for example reactive astrocytes have been repeatedly identified as a component of senile amyloid plaques in the cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. from 1988 [9-12]. But not long ago, 30 years later, the theory implicating amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease was still the dominant theory.

This may correspond to what was known at the time, as astrocytes and microglia were then considered almost useless. This is, however, something astonishing to say, even at the end of the 20th century, since these cells clearly constitute a large part of the matter of the brain and the spine.

It started off well for the application of cell biology in neurodegenerative diseases, with an apparent success in 1998, when mutations in the SOD1 gene were implicated in familial ALS.

Unfortunately, it quickly became clear that SOD1 mutations only affect a small number of familial cases of ALS and they presented a great diversity with a life expectancy varying from one year in severe forms to 10 years or more in other less dangerous mutations.

Although the vast majority of articles on ALS concern SOD1, mutations in SOD1 therefore appear to be an epiphenomenon in the case of ALS, both because of their very low frequency but also for the diversity of phenotypes.

The main cause of familial ALS was not found until 2011, 20 years after promises from like those of the human genome project. Mutations in C9orf72 create repeats motifs in some proteins. Geneticists had been investigating familial ALS for about 30 years, and the lack of progress raised concerns. C9orf72 is not a gene, it is an area that was considered non-coding until then, hence the difficulty in using molecular biology tools.

Strangely enough, these pattern repeats are also present in everyone, but more pronounced in the elderly. They are also present in other diseases. So it seems that the number of repetitions could involve different diseases.

Molecular biology has proposed more than a hundred genes as participating in the etiology of ALS and has proposed thousands of drugs and at one point scientists started to be reluctant to incriminate even more genes in ALS (or Alzheimer's, etc.).

Thus, for scientists who had decided to pursue a career in molecular biology and who thought they were in an impasse, there was a strong temptation to turn towards translation and post-translational modifications of proteins.

We were then inundated with studies claiming that this or that protein was poorly translated, poorly conformed or poorly localized in the cell. The subject of misfolded proteins even created small wars between biologists (Tauiste against Baptiste). The problem is that most of these proposed proteins are found in most neurodegenerative diseases, Tau, TDP-43, etc [1]. So they do not seem specific to ALS, Alzheimer's or Parkinson's. If they are not specific, how can they be causative of one, but not other neurodegenerative diseases?

There are however alternative views among scientists working in the field of ALS, one is that ALS starts in muscles, not in the brain. This hypothesis has been both * proven and disproved * on several occasions, which seems very confusing from a non-specialist's point of view.

But anyway this hypothesis does not explain what would cause the muscle disease, it only pushes the explanation of this muscle wasting, away to future works.

If we think globally, like a doctor, there are two common reasons for cells to die (be it muscle cells or upper motor neurons). There is no need for extremely sophisticated explanations for this.

Either their blood supply is faulty (see the similarity to stroke above) or the cellular metabolism is faulty (hence the appearance of reactive stress).

It seems that articles on a defective metabolism are quite rare, but they could be found, here are examples [7-8, 13]. Some articles have even blamed the use of methionine sulfoximine (MSO) in a now abandoned flour bleaching process [8] or other environmental contaminants as contributing factors to ALS.

It is surprising that although there have been many publications on these two topics, no clinical trial has tried drugs linked to metabolic dysfunction.

For example, clinical trials could study:

* MAO-B inhibitors [2],

* Methionine sulfoximine (MSO) which dramatically extended the lifespan of a SOD1 G93A mouse model for ALS. [3]

* Pathological inhibition of glutamine synthetase (GS). In the brain, GS is exclusively localized in astrocytes where it is used to maintain the glutamate-glutamine cycle, as well as nitrogen metabolism. Changes in GS activity have been identified in a number of neurological conditions [4].

* Methionine sulfoximine (MSO), a well-characterized glutamine synthetase inhibitor, is a convulsant, particularly in dogs, but shows significant therapeutic benefits in animal models for several human diseases [5, 6]

* But also many other drugs related to the brain and spine metabolism.

[1] https://www.statnews.com/2019/06/25/alzheimers-cabal-thwarted-progress-toward-cure/

[2] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32852645/

[3] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28323087/

[4] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27885636/

[5] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28292200/

[6] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24136581/

[7] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7148401/

[8] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10052866/

[9] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3196922/

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2531723/

[11] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2808689/

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5996928/

[13] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5063041/

[14] https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Amyotrophic+Lateral+Sclerosis&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search&phase=2&phase=3

[15] https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Amyotrophic+Lateral+Sclerosis&age_v=&gndr=&type=Intr&rslt=&Search=Apply

Source:

Source:

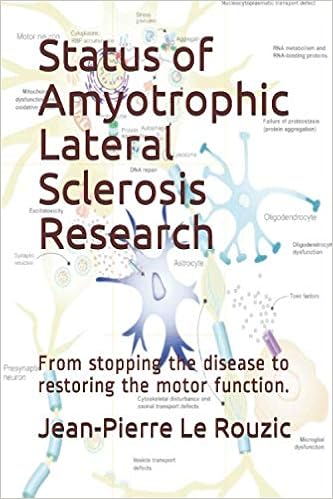

La SLA détruit les cellules nerveuses qui contrôlent les mouvements musculaires. Les patients deviennent généralement handicapés. On distingue généralement les patients à progression lente (avec une meilleure espérance de vie) de ceux qui ont une progression rapide. Les patients ayant une progression rapide meurent dans les cinq ans suivant leur diagnostic.

La SLA détruit les cellules nerveuses qui contrôlent les mouvements musculaires. Les patients deviennent généralement handicapés. On distingue généralement les patients à progression lente (avec une meilleure espérance de vie) de ceux qui ont une progression rapide. Les patients ayant une progression rapide meurent dans les cinq ans suivant leur diagnostic.