These days, major news stories about neurodegenerative diseases are rare. One headline in the trade press claims: "Harmless Virus Could Trigger Parkinson's Disease."

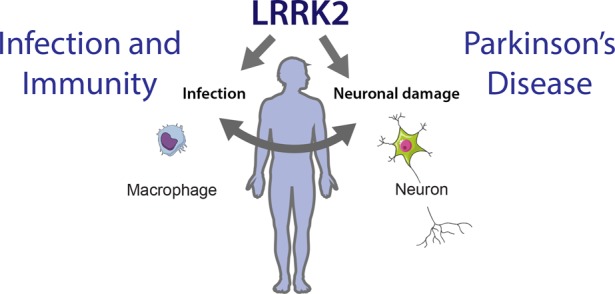

Most cases of Parkinson's disease are idiopathic, meaning the cause is unknown. However, several genetic mutations can also lead to this neurodegenerative disease, with approximately 20 to 25 percent of cases having a genetic cause. One of these mutations is in the gene encoding LRRK2, which can result in enzyme levels two to three times higher than normal. These mutations are more common in North African, Arab, Berber, Chinese, and Japanese populations.

There is some good news coming out on this topic, but I'll talk about another publication.

Every viral infection alters the genetic material of some (but not all) cells in our body. This is how a virus forces the host cell to rapidly produce thousands of copies of itself. In most cases, viruses are first abruptly eliminated by the innate immune system, killing the host cell. The adaptive immune system uses a more intelligent mechanism, producing specific antibodies that bind to the virus and often render it non-infectious. This process is called humoral immunity. The LRRK2 protein is highly expressed in immune system cells, particularly in response to bacterial pathogens like Salmonella.

The hypothesis that some neurodegenerative diseases are caused by viral infections is attractive because it could explain why these diseases appear with age and why they affect the nervous system, as many viruses tend to accumulate there with age.

In a new study, researchers analyzed brains provided by the Rush Alzheimer's Research Center (RADC) in Chicago, from 10 autopsied Parkinson's patients and 14 non-PD patients. They found traces of human pegylated virus (HPgV) in five Parkinson's brains, but none in healthy brains. Human pegylated virus is a virus related to hepatitis C. The virus has also been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson's disease patients, but not in the control group. However, the small sample size makes these results inconclusive.

Next, perhaps seeking stronger evidence, the researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,393 participants in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative, a biological sample bank for Parkinson's disease research. Only about 1% of Parkinson's patients had HPgV in their blood, which is consistent with the infection rate in the general population.

Nevertheless, the scientists say that people infected with the virus exhibited different immune signals, particularly those with a mutation in the LRRK2 gene. They explained that since mutations in the LRRK2 gene are known to influence immune signaling, autophagy, and viral processing, these genotype-specific responses suggest that host genetics and viral interactions could influence immune responses to human pegivirus, promoting neuroinflammation and the development of Parkinson's disease.

At this point, I'm confused; they performed two experiments, one not significant and the other negative, but in the article, the scientists still suggest a possible link between Parkinson's disease and human pegivirus. However, the headline and abstract (which will likely be the only parts colleagues read) are much less definitive: they only suggest that human pegivirus alters the transcriptomic profiles of patients with Parkinson's disease.

This is a far cry from the headlines in the trade press: "Harmless virus might trigger Parkinson's disease."