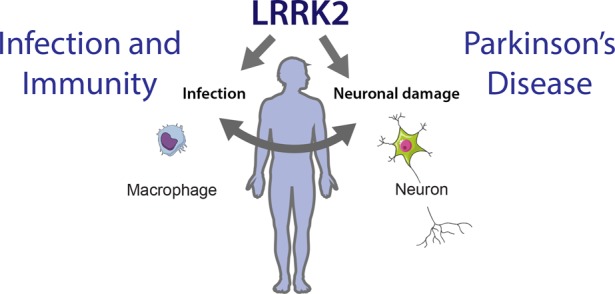

Although effective symptomatic therapies have been developed for Parkinson's disease (PD), treatments that modify the disease itself still do not exist.

Drug repurposing studies help identify potential disease-modifying treatments. One advantage of drug repurposing is that, since these drugs are already approved, their safety profiles are known. However, further industry investigation is unlikely because companies hesitate to invest in drugs whose intellectual property is owned by others. Generally, they might consider repurposing their own drugs, which extends patent life by claiming new uses. This can also lead to questionable combinations of approved drugs just to file a patent.

In an issue of Neurology, Tuominen et al. publish a nationwide observational cohort study in Norway aiming to identify new candidates for disease modification in Parkinson's disease. They analyzed Norwegian health registries from 2004 to 2020 to identify people with Parkinson's. The study included 14,289 individuals and found 23 drugs among a total of 219 drugs associated with a reduced eight-year mortality risk.

Nonetheless, this reduction remains minor, and there is no proof that these drugs caused improved survival.

The authors note that, although their findings are exploratory and cannot be directly applied clinically yet, the identified drugs could be considered for future clinical trials. Indeed, funding should be sought for these future trials, and since it is almost always private investors who finance clinical trials, they would require more information before making any commitments.

The authors note that, although their findings are exploratory and cannot be directly applied clinically yet, the identified drugs could be considered for future clinical trials. Indeed, funding should be sought for these future trials, and since it is almost always private investors who finance clinical trials, they would require more information before making any commitments.

However, this study has notable strengths compared to similar studies. Tracking specific disease milestones is crucial for evaluating the effects of potential disease-modifying treatments.

For nearly all of the 23 drugs discussed by Tuominen et al., the adjusted eight-year mortality curves for Parkinson's patients and healthy controls diverged and showed different slopes, suggesting these compounds may have a disease-modifying effect. This pattern has not been observed in other trials testing potential disease-modifying drugs.

When interpreting Tuominen et al.'s results, it is important to remember that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. A drug associated with lower mortality does not automatically prove that it caused the reduction.

On the one hand, the decreased mortality might simply reflect that healthier Parkinson's patients are more likely to be prescribed these drugs. For example, patients using tadalafil (for erectile dysfunction) may have better overall health and longer survival.

On the other hand, for the more difficult cases, some physicians may have focused solely on treating essential symptoms rather than prescribing a large number of medications.

Additionally, the number of patients in the "treatment" group is often small; for instance, only 170 patients used Levothyroxine sodium.