I often complain that neurodegenerative literature is of low quality and has little usefulness. Here is an article that may be very different.

It's known that in some diseases, like cord spine injury, some motor neurons reverse to an immature state, and it is thought that this may have a protective effect. The authors reflected that inducing vulnerable mature motor neurons into an immature state might be beneficial, and they tested this hypothesis in-vitro and on mice. Two key transcription factors, ISL1 and LHX3, are the master regulators of the immature motor neuron gene expression program. These factors are naturally expressed during embryonic development but are typically turned off in mature neurons. Yet ISL1 and LHX3 are not the only proteins involved in the maturation process of motor neurons. 7,000 genes change their expression significantly throughout postnatal motor neuron maturation

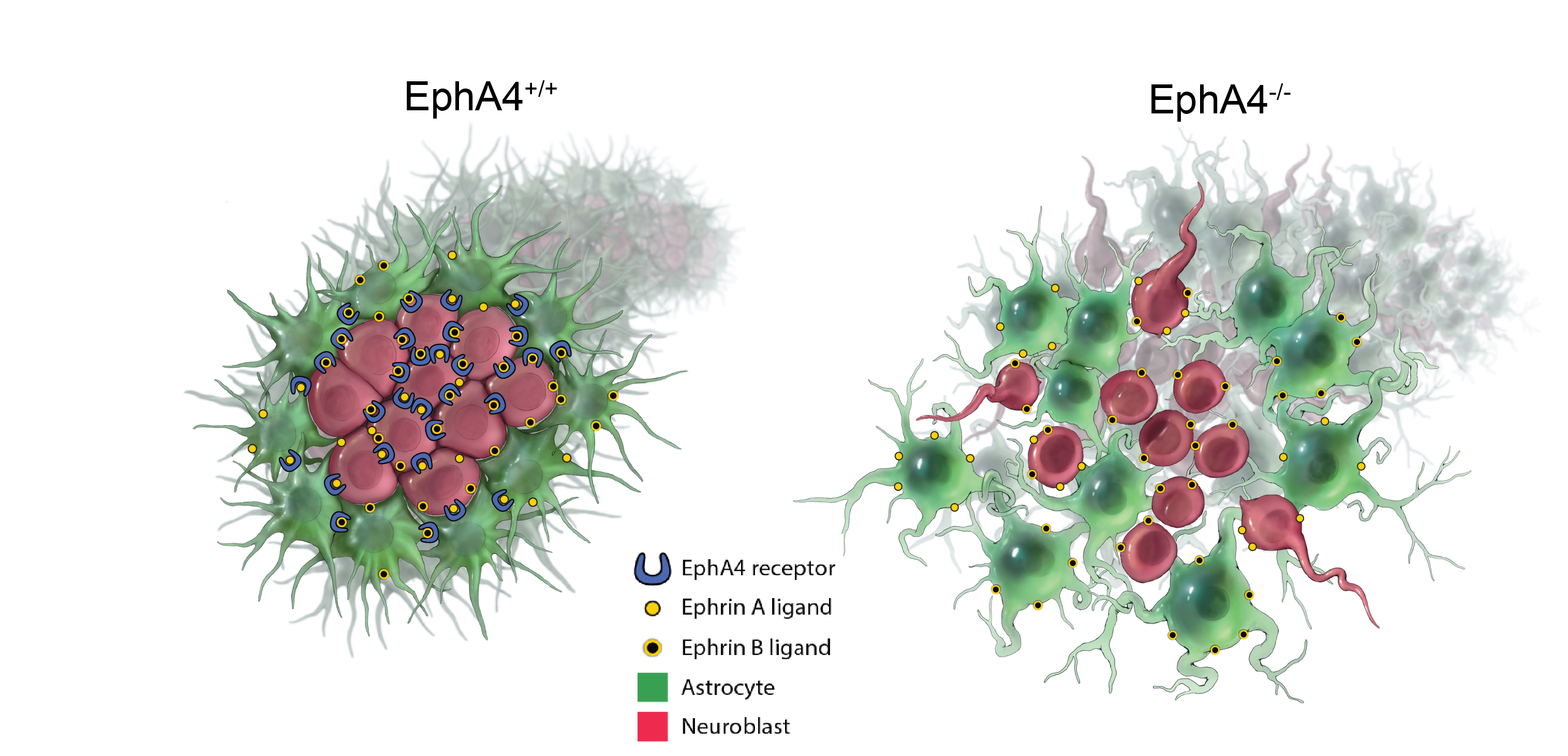

The developmental stages from a stem cell to a mature motor neuron follow these steps: The process begins with neural stem cells in the developing spinal cord. These cells can develop into various types of neurons and glial cells. Under the influence of signaling molecules (like Sonic Hedgehog), the neural progenitors become motor neuron progenitors, which are now committed to the motor neuron lineage. These progenitor cells multiply. Then these progenitors stop dividing and differentiate into neuroblasts.

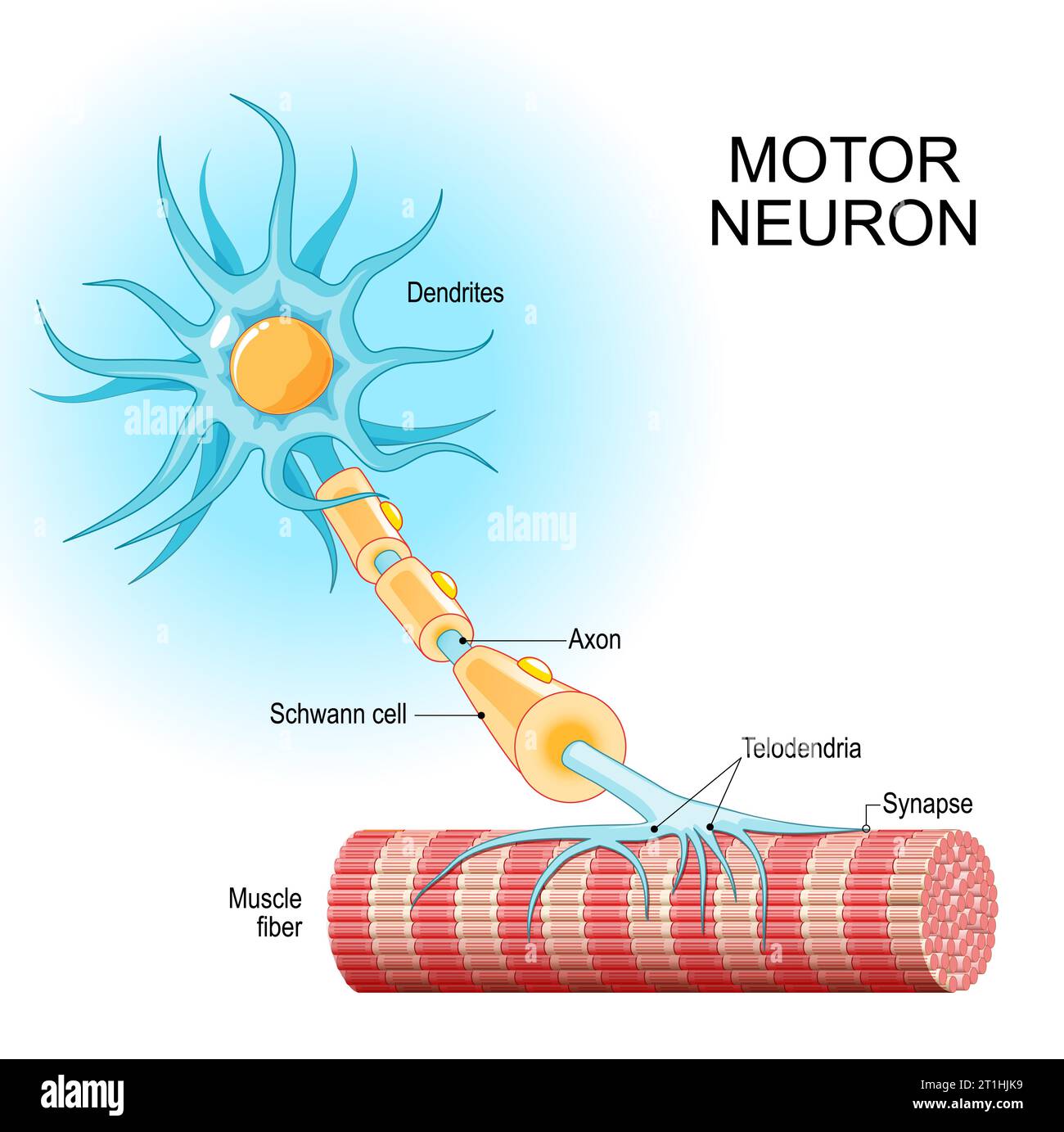

At this stage, neuroblasts express key transcription factors like ISL1 and LHX3, which establish the fundamental identity of the motor neuron. The neuroblast begins to resemble more to a motor neuron: They extend a long axon out of the spinal cord towards their target muscle. The cell also starts to acquire its specific electrical properties. Then the neuron reaches its target muscle, forms a neuromuscular junction, and becomes a fully functional, electrically active cell. At this point, the early master regulators like ISL1 and LHX3 are largely downregulated, and the neuron enters its final, mature state.

At this stage, neuroblasts express key transcription factors like ISL1 and LHX3, which establish the fundamental identity of the motor neuron. The neuroblast begins to resemble more to a motor neuron: They extend a long axon out of the spinal cord towards their target muscle. The cell also starts to acquire its specific electrical properties. Then the neuron reaches its target muscle, forms a neuromuscular junction, and becomes a fully functional, electrically active cell. At this point, the early master regulators like ISL1 and LHX3 are largely downregulated, and the neuron enters its final, mature state.

The authors designed a genetic therapy with an AAV virus vector to make mature neurons express two proteins that are only expressed in the immature state.

The AAVs were specifically engineered to target motor neurons. In the study conducted on mice, the administration mode of the AAV viral vector was able to specifically infect the spinal motor neurons.

Once inside the mature motor neurons, the AAV released the therapeutic genes. This caused the neurons to begin expressing ISL1 and LHX3 again

By re-expressing ISL1 and LHX3, the researchers essentially re-activate that original "immature" genetic program. This causes the mature neuron to revert to a state that is genetically and functionally similar to its younger self, with renewed resilience and stress-coping abilities.

They believe that turning on the immature genetic program essentially re-awakens the neuron's dormant ability to regrow and repair itself. While mature neurons in the central nervous system have very limited regenerative capacity, the authors are suggesting that ISL1 and LHX3 could be flipping a switch that bypasses this limitation.

The authors designed a genetic therapy with an AAV virus vector to make mature neurons express two proteins that are only expressed in the immature state.

The AAVs were specifically engineered to target motor neurons. In the study conducted on mice, the administration mode of the AAV viral vector was able to specifically infect the spinal motor neurons.

Once inside the mature motor neurons, the AAV released the therapeutic genes. This caused the neurons to begin expressing ISL1 and LHX3 again

By re-expressing ISL1 and LHX3, the researchers essentially re-activate that original "immature" genetic program. This causes the mature neuron to revert to a state that is genetically and functionally similar to its younger self, with renewed resilience and stress-coping abilities.

They believe that turning on the immature genetic program essentially re-awakens the neuron's dormant ability to regrow and repair itself. While mature neurons in the central nervous system have very limited regenerative capacity, the authors are suggesting that ISL1 and LHX3 could be flipping a switch that bypasses this limitation.

This was not achieved in a linear process; On the contrary, the study tells of multiple steps to study what was achieved and to learn how to progress.

Their study focussed on SOD1 ALS, so they used a SOD1 mouse model to study dysregulation of SQSTM1 and how ISL1 and LHX3 expression influence it. Large, round aggregates of SQSTM1 (termed “round bodies”) are detectable in the cytoplasm of SOD1 ALS motor neurons At transduction efficiencies greater than ∼80%, SQSTM1 round bodies were almost completely abrogated, pointing to a cell-autonomous effect of ISL1 and LHX3 re-expression on SQSTM1 pathology.

The transfected mice survived longer than the control ones, and the effect is much more pronounced in females than in males. Yet that was not a cure, and the study was only on SOD1 ALS; there are multiple types of ALS, so we don't have a clear idea of the impact of this therapy on other genetic/familial and sporadic ALS. Also, the authors found that the expression of ISL1 and LHX3 lasts only two weeks, so there is little time for the therapy to work. It would be interesting to see a similar study on the other species of nervous cells. The authors also highlight that it is unknown if this therapy would be effective late stages of the disease when motor neuron degeneration is underway and non-cell-autonomous factors such as neuroinflammation contribute to clinical progression.

The number of mice was also very low (8 mice in the treatment group and 6 mice in the control group), to the point where it is not statistically significant.

But for me, this study has a potential that most other studies have not: They try hard to heal motor neurons, not simply to repress some of the hundreds of genes involved in ALS. Gene KO approaches are lazy; it's shooting in the dark. This study is a great step forward, even if therapy is probably one or two decades away.