Il y a environ 15 000 articles scientifiques par an au sujet de la SLA et chaque année environ une cinquantaine de ces articles clament avoir fait un progrès décisif dans la lutte contre cette maladie. On pourrait se réjouir de cet intérêt scientifique et des ressources immenses qui seraient apparemment impliquées dans cette recherche.

En fait il y a une découverte majeure dans le domaine de la SLA seulement toutes les quelques années.

D'où vient cette différence entre ces deux faits? La publication d'articles scientifiques est un moyen d'obtenir des fonds et de faire progresser une carrière. Si un auteur veut publier rapidement un article, mais en évitant d'être scruté par des milliers de lecteurs, il est tentant de publier dans un domaine obscur où le nombre de spécialistes est très réduit par rapport à un domaine comme la recherche sur le cancer.

De plus, nombre de scientifiques ne lisent pas les articles publiés par leurs pairs, ils se contentent de lire l'abstract et appliquent des filtres mentaux. Il est alors tentant pour un auteur malhonnête de publier un abstract qui exagère considérablement les résultats obtenus. Et c'est sans compter le dossier de presse de l'université qui en général est tellement dithyrambique qu'il en est comique, sauf pour les malades et leur famille.

Diverses études ont montré qu'un tiers des articles scientifiques dans le domaine biologique/médical ne sont pas reproductibles.

L'article dont nous parlons aujourd'hui est un rafraichissement considérable par rapport à ces pratiques nauséabondes. Les auteurs, Morgan Highlander et Sherif Elbasiouny, y examinent une étude récente d'Ahmed et al.,

qui affirme qu'une forme de stimulation électrique spinale (« DCS multivoies ») améliore considérablement la survie et la fonction motrice chez la souris SOD1-G93A, un modèle de SLA. Bien que les effets rapportés semblent impressionnants – notamment une amélioration de la survie de 74 % –, les auteurs affirment qu'un examen détaillé de la méthodologie révèle plusieurs problèmes critiques qui fragilisent considérablement ces conclusions.

Utilisation trompeuse des indicateurs de survie

Le chiffre principal de l'étude (survie prolongée de 74 %) est basé sur le délai entre l'apparition des symptômes et l'arrêt du traitement, et non sur la durée de vie totale. Cet indicateur n'est pas une mesure standard de la survie dans la recherche sur la SLA et dépend fortement de la méthode de détection de l'apparition des symptômes – une évaluation qui peut être subjective. Lorsque la durée de vie totale est examinée directement, l'amélioration réelle n'est que d'environ 5 %, et non de 74 %.

Cela est évident quand on regarde les figures de l'article d'Ahmed et al.

Analyses statistiques contestables

Analyses statistiques contestables

Les auteurs de l'article d'Ahmed et al. appliquent des tests statistiques sans vérifier que les données respectent les hypothèses requises pour ces tests. Le groupe non stimulé ayant enregistré deux décès exceptionnellement précoces, le bénéfice de survie surestimé pourrait être largement dû à ces valeurs aberrantes.

Détection non validée et probablement tardive de l'apparition des symptômes

La date rapportée d'apparition des premiers symptômes semble bien plus tardive que celle généralement observée, ce qui suggère que les symptômes ont pu être détectés beaucoup trop tard.

Contradictions et incohérences dans les données supplémentaires

Une expérience supplémentaire, où la stimulation a débuté à un âge fixe, n'a montré aucun bénéfice en termes de survie.

Les résultats concernant la fonction motrice proviennent de seulement 8 des 48 animaux, sans explication des critères utilisés pour la sélection de ces 8 animaux. Aucun test statistique n'a été réalisé et le test de marche sur grille utilisé dans l'étude n'est ni standard ni validé pour les modèles de SLA. Les scores étant uniquement exprimés en fonction du « jour après l'apparition des symptômes », les résultats ne peuvent être comparés aux schémas d'évolution connus de la maladie.

Preuves histologiques insuffisantes L'analyse tissulaire, censée mettre en évidence une réduction des marqueurs de la maladie et la préservation des neurones, manque de précisions méthodologiques essentielles. Des éléments clés tels que la stratégie d'échantillonnage, les critères d'imagerie et les contrôles ne sont pas décrits. Certains résultats semblent clairement influencés par des valeurs aberrantes. Les contrôles de base (par exemple, la confirmation de l'identité des neurones ou la normalisation des signaux de fluorescence) sont absents. Globalement, les données histologiques n'apportent pas d'éléments probants en faveur des effets du traitement.

Conclusion

Morgan Highlander et Sherif Elbasiouny soutiennent que l’étude d’Ahmed et al. ne répond pas aux exigences de rigueur attendues dans la recherche préclinique sur la SLA. Le bénéfice en termes de survie est surestimé, les analyses statistiques sont erronées, la méthode de détection de l’apparition des symptômes n’est pas validée et les résultats fonctionnels et histologiques sont peu étayés.

Sachant que des résultats précliniques surestimés ont déjà contribué à l’échec d’essais cliniques sur la SLA, les auteurs, Morgan Highlander et Sherif Elbasiouny, insistent sur l’importance de méthodologies robustes et transparentes. Ils préconisent une révision substantielle de l’analyse et de la présentation des résultats de l’étude avant que sa valeur thérapeutique ne puisse être évaluée de manière fiable.

The authors found that key immune signaling proteins, specifically those containing Death Fold Domains (DFDs) (like ASC, FADD, BCL10, MAVS, TRADD), exist in a unique physical state inside our cells called metastable supersaturation. These full-length adaptors retain nucleation barriers and are able to exist supersaturated in cells. In contrast, many receptors and effectors do not. This localizes the “spring-loaded” behaviour to central adaptors that link receptor sensing to downstream cell-fate decisions.

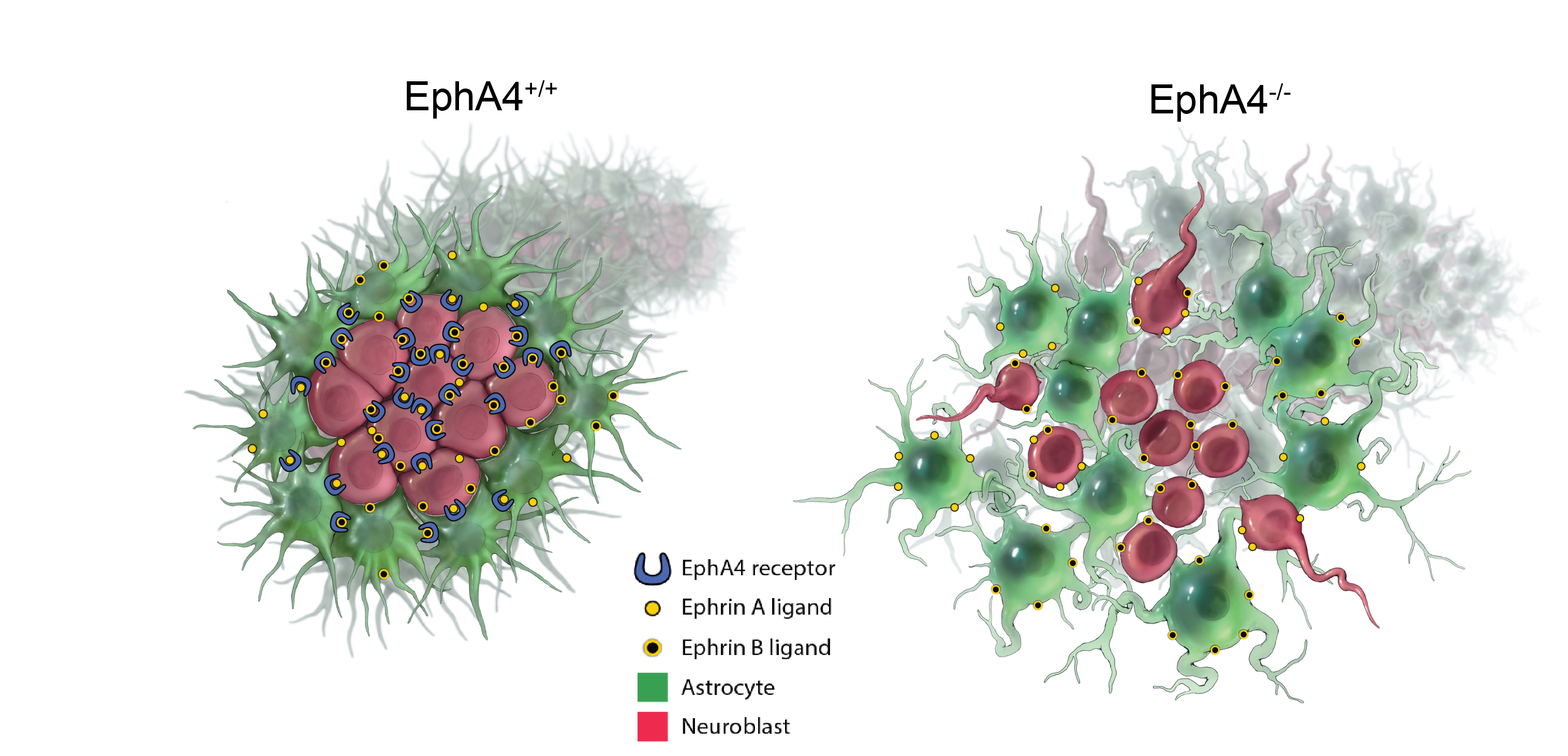

The authors found that key immune signaling proteins, specifically those containing Death Fold Domains (DFDs) (like ASC, FADD, BCL10, MAVS, TRADD), exist in a unique physical state inside our cells called metastable supersaturation. These full-length adaptors retain nucleation barriers and are able to exist supersaturated in cells. In contrast, many receptors and effectors do not. This localizes the “spring-loaded” behaviour to central adaptors that link receptor sensing to downstream cell-fate decisions. At this stage, neuroblasts express key transcription factors like ISL1 and LHX3, which establish the fundamental identity of the motor neuron. The neuroblast begins to resemble more to a motor neuron: They extend a long axon out of the spinal cord towards their target muscle. The cell also starts to acquire its specific electrical properties. Then the neuron reaches its target muscle, forms a neuromuscular junction, and becomes a fully functional, electrically active cell. At this point, the early master regulators like ISL1 and LHX3 are largely downregulated, and the neuron enters its final, mature state.

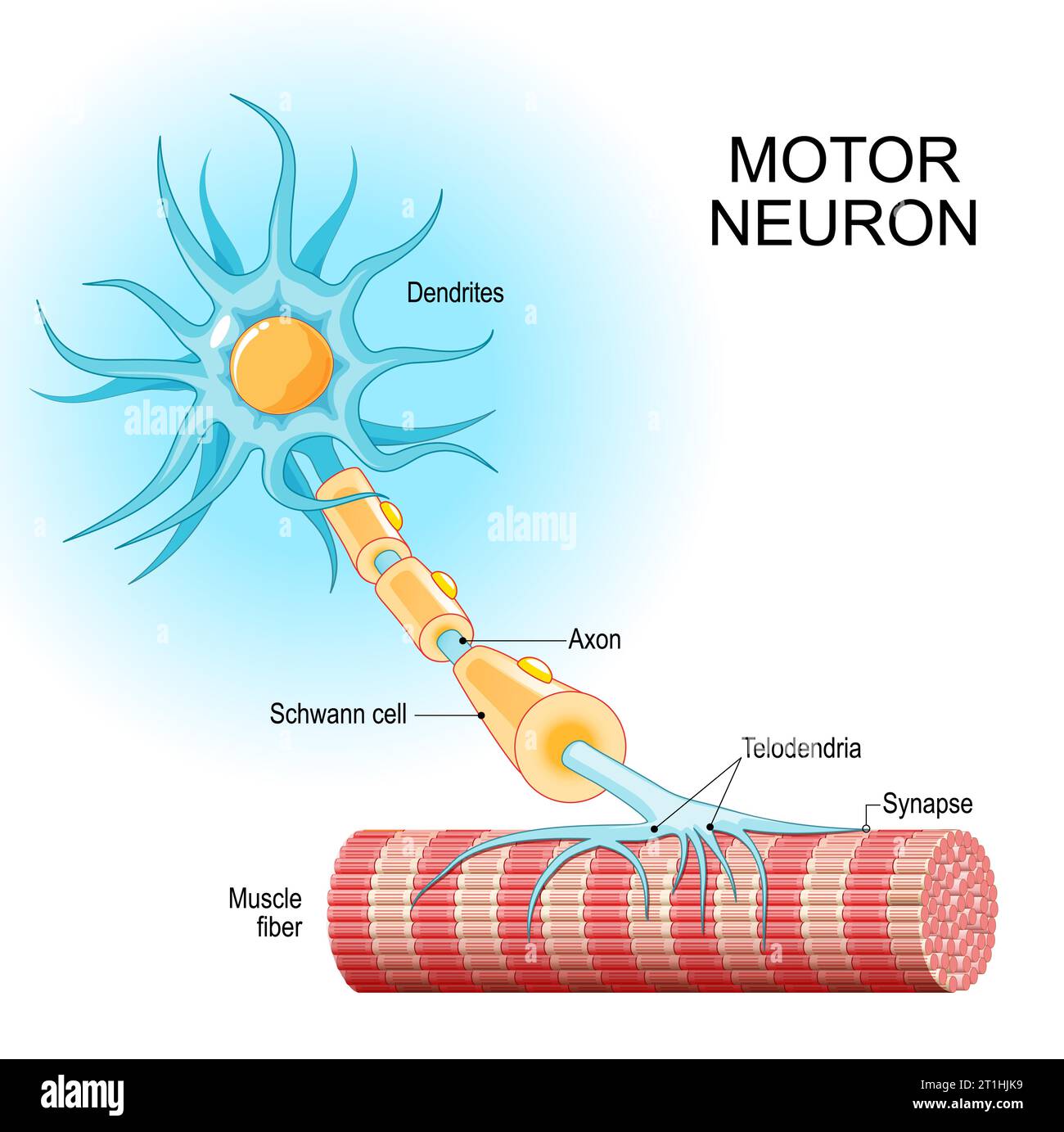

At this stage, neuroblasts express key transcription factors like ISL1 and LHX3, which establish the fundamental identity of the motor neuron. The neuroblast begins to resemble more to a motor neuron: They extend a long axon out of the spinal cord towards their target muscle. The cell also starts to acquire its specific electrical properties. Then the neuron reaches its target muscle, forms a neuromuscular junction, and becomes a fully functional, electrically active cell. At this point, the early master regulators like ISL1 and LHX3 are largely downregulated, and the neuron enters its final, mature state.

The authors designed a genetic therapy with an AAV virus vector to make mature neurons express two proteins that are only expressed in the immature state.

The AAVs were specifically engineered to target motor neurons. In the study conducted on mice, the administration mode of the AAV viral vector was able to specifically infect the spinal motor neurons.

Once inside the mature motor neurons, the AAV released the therapeutic genes. This caused the neurons to begin expressing ISL1 and LHX3 again

By re-expressing ISL1 and LHX3, the researchers essentially re-activate that original "immature" genetic program. This causes the mature neuron to revert to a state that is genetically and functionally similar to its younger self, with renewed resilience and stress-coping abilities.

They believe that turning on the immature genetic program essentially re-awakens the neuron's dormant ability to regrow and repair itself. While mature neurons in the central nervous system have very limited regenerative capacity, the authors are suggesting that ISL1 and LHX3 could be flipping a switch that bypasses this limitation.

The authors designed a genetic therapy with an AAV virus vector to make mature neurons express two proteins that are only expressed in the immature state.

The AAVs were specifically engineered to target motor neurons. In the study conducted on mice, the administration mode of the AAV viral vector was able to specifically infect the spinal motor neurons.

Once inside the mature motor neurons, the AAV released the therapeutic genes. This caused the neurons to begin expressing ISL1 and LHX3 again

By re-expressing ISL1 and LHX3, the researchers essentially re-activate that original "immature" genetic program. This causes the mature neuron to revert to a state that is genetically and functionally similar to its younger self, with renewed resilience and stress-coping abilities.

They believe that turning on the immature genetic program essentially re-awakens the neuron's dormant ability to regrow and repair itself. While mature neurons in the central nervous system have very limited regenerative capacity, the authors are suggesting that ISL1 and LHX3 could be flipping a switch that bypasses this limitation. De façon similaire, la force des souris modifiés génétiquement est nettement plus basse au début du traitement qu’à la fin, c’est l’inverse de ce qu’on pourrait attendre d’une souris qui serait de plus en plus affaiblie.

Et pourquoi ce groupe de souris aurait-il une force plus faible au début de l’expérience ? S’il n’y a pas de sélection à priori, les différents groupes de souris (traités et non traités) devraient avoir la même force.

De façon similaire, la force des souris modifiés génétiquement est nettement plus basse au début du traitement qu’à la fin, c’est l’inverse de ce qu’on pourrait attendre d’une souris qui serait de plus en plus affaiblie.

Et pourquoi ce groupe de souris aurait-il une force plus faible au début de l’expérience ? S’il n’y a pas de sélection à priori, les différents groupes de souris (traités et non traités) devraient avoir la même force. What should we consider about all this? Maybe we should ask why scientists are searching for new drugs instead of focusing on compounds of drugs that have already shown some effects. Perhaps everyone wants to get rich, so they avoid exploring drugs that can't be patented.

What should we consider about all this? Maybe we should ask why scientists are searching for new drugs instead of focusing on compounds of drugs that have already shown some effects. Perhaps everyone wants to get rich, so they avoid exploring drugs that can't be patented.